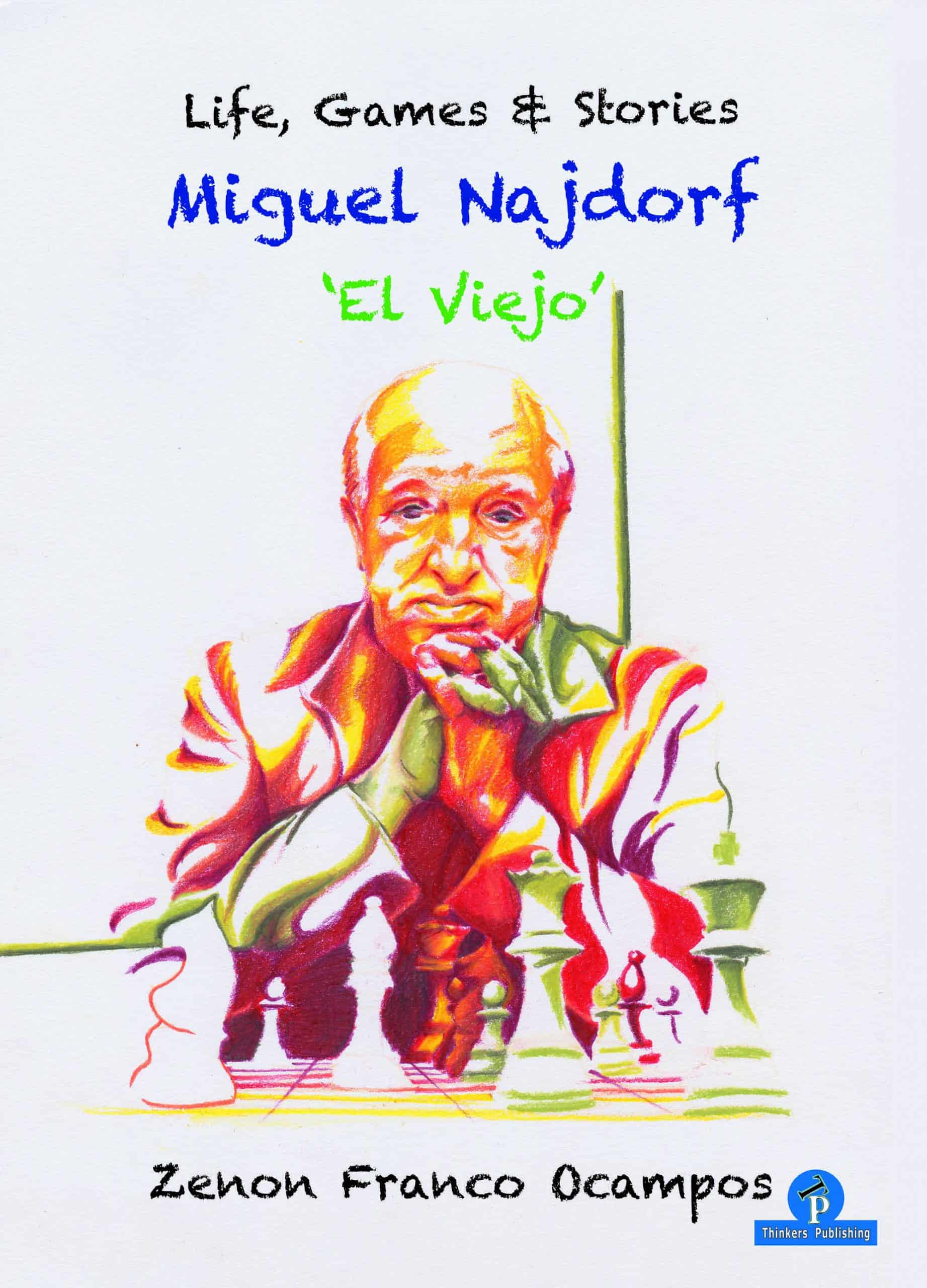

Franco: Miguel Najdorf - El Viejo

Writing about Miguel Najdorf is one of my greatest pleasures as a chess journalist and writer. Having known him is a privilege of which I quickly became aware, along with Sergio Giardelli, who had more dealings with him than I did. A few years ago we agreed that both of us could say “I knew Mozart”, not the real Mozart, of course, but referring to someone who reached the highest point of the discipline he embraced. Najdorf did so with the utmost passion.

I never felt able to call him “el Viejo” (literally “The old man”), as everyone, himself included, called him; I think it sounded disrespectful to me because of my Guarani roots, although obviously no disrespect was implied.

The first time I heard of him was through the magazine “Ajedrez”, and later through the occasional annotations of my mentor Bernardo Wexler, who had a high regard for Don Miguel’s chess strength.

I remember that in the 1970 Siegen Olympiad, where Najdorf played on the top board, and once again had to face the best players in the world, Wexler said, “If Najdorf wants it so, nobody can beat him, but he will want to win, and then he might lose; but if he plays for a draw, nobody can beat him”.

At that time I was unaware of the strength of the masters. The first time I went to the Club Argentino de Ajedrez (Argentine Chess Club) I watched several masters playing blitz games (or “ping-pong” games, as they used to say over there) and for me they were all very good, of similar strength. When I asked him who was the best, Wexler did not hesitate: “Najdorf, Najdorf.”

On another occasion Wexler mentioned one of Najdorf’s characteristic traits: his extreme competitiveness. He recalled that when he was eighteen he had once shared first place with Najdorf himself. Wexler was then only a second-category player and he was on cloud nine. Najdorf wanted to play a tie-break, which Wexler declined to do, explaining that he was very excited, quite unable to play, but Najdorf insisted over and over again, said he would give him the entire first prize if he played, etc.

He insisted so much that he persuaded Wexler to play and Najdorf won the tie-break. Not until many years later did Wexler manage to get over it. If we are completely honest, this aspect of Najdorf’s personality made him unpopular, but this is only one aspect of his personality.

In his book Chess Duels Seirawan speaks aff ectionately and admiringly about Garry Kasparov, explaining that there are “two Garrys, the Good and the Bad”, and that “if there is one person in the whole world I would want to represent chess and to speak to a sponsor, it is the Good Garry. He is witty, charming, erudite…”, while “the Bad Garry can be surly, angry and rude, making the most committed sponsor put his checkbook away and run for the nearest exit.”

This description of Kasparov reminds me a little of Najdorf, not exactly, but in Don Miguel there were also two personalities. One was Najdorf the competitor; as Oscar Panno commented, “when he was competing, the others were not rivals or adversaries, they were enemies, and he treated them as such.”

On the other hand, in his personality away from the board, in other words most of the time, Najdorf was pleasant, amusing, enthusiastic, interested in everything, with his strengths and weaknesses, like everyone else, but, as I was able to confi rm on many occasions, basically a very good-hearted person.

Liliana Najdorf, one of his daughters and author of the book “Najdorf × Najdorf”, described him like this: “to say he was larger than life strikes me as an understatement. I look for synonyms that will help me to defi ne him and in those words I find him: passionate, disproportionate, ostentatious, gigantic, extraordinary, overwhelming, marvellous. Wise”.

Just as accurate is the image that Ricardo Calvo once gave of Don Miguel in the Spanish magazine “Jaque”: “Najdorf is not someone who passes unnoticed… He has a kind of strength, or energy, or vitality, call it what you will, which draws you, attracts attention, complicates or simplifies matters, (as a rule, it seems to me he complicates things), and like a whirlwind stirs up even the seemingly most structured of quiet backwaters of the spirit, of anyone who through good luck or misfortune has burst into his field of activity… He is forever faithful to his own truth: that vital enthusiasm which he appears to draw from the most primitive layers of his being, which penetrates it and which, passing through him, destabilizes anyone who accompanies him… He is neither good nor bad, that’s just the way he is…”

In any case, as I write this book I am reminded of something Jorge Amado said, as reported to me by Jaime Sunye; when Amado was criticised for saying good things about a friend (whose ideas were completely opposed to his own), Amado said something like “I speak about what is good about him, let others speak about what is bad.”

Oscar Panno said that Najdorf reminded him of Don Quixote, in the part of the book where he tells Sancho Panza, “Wherever I am, that is where the head of the table is going to be.” Najdorf himself commented in a book that he had begun to write, “You can’t win unless you are a bit conceited. So the reader must forgive me if I sometimes seem to be something of an egomaniac”.

And yes he was. He could grow suddenly angry, and just as rapidly calm down. He quite often sang his own praises. He could be argumentative, an interfering busybody, etc., whatever we might choose to say, but he was also capable of apologising and he was the greatest populariser of chess in Argentina.

Not only from his column in the “Clarín” newpaper, as his friend Luis Scalise recalls. In every town he visited in inland Argentina, even the smallest, if he saw that there was no club, in his farewell speeches he never failed to make a request to the authorities: “Mr Mayor, please, how is it that a town like this does not have a chess club…?”; that was one of his ever-present requirements.

He successfully overcame the most terrible setbacks, as few are capable of doing, and as regards his meddlesome nature, on the great majority of occasions it was because he wanted to help, according to his way of seeing things, of course.

I had the great good fortune to get to know him, fi rst through magazines and books, later by watching him play and later still by playing against him and being his frequent sparring partner in the marathon blitz sessions which were always a part of his life.

How could anyone not remember Najdorf’s sayings, repeated again and again, as entertaining as the first time he said them: “I had a ve-e-ery wise aunt, who used to say, better a pawn up than a pawn down”, laughing. “There are two ways of winning at chess, when you play well and your opponent plays badly, or when you play badly and your opponent plays worse”. “First the idea, then the move!”, etc., etc.

We shall summarise nothing less than seventy years of Don Miguel’s chessplaying life , and we shall take a brief look back at the history of chess in Argentina, sometimes seen through Don Miguel’s eyes, thanks to his own writings. All of this, and his games, will be discussed in the book.

Najdorf was the most important Argentinean chessplayer and he was an exceptional person; I feel privileged to have known him and to have spent time with him.

720 Seiten, kartoniert, Verlag Thinkers Publishing

Anmelden